Why Everything is Not a Psyop

Why you don’t need a mastermind to get a conspiracy-shaped world when you have economics and Adam Smith

There’s a sentence that keeps appearing in analysis of QAnon, disinformation, and political radicalisation:

“This is too coordinated to be organic.”

It sounds reasonable. It sounds serious. It sounds like the kind of conclusion a responsible adult would reach when confronted with scale, coherence, and repetition.

It is also very often wrong.

Not because foreign interference doesn’t exist.

Not because bad actors aren’t bad.

But because coordination is no longer the hard part.

In a modern attention economy, coordination is what naturally emerges when many actors optimise for the same rewards.

This article explains why we keep mistaking market convergence for hidden orchestration, using QAnon, Mike Flynn, and a recent high-profile Substack investigation as concrete examples, and why invoking “psyops” increasingly functions as a vibes-based explanation rather than a necessary one.

I’m going to use maths where it helps, not to impress, but because it forces clarity.

1. Start with the outcome, not the villain

Let’s describe the world we’re trying to explain.

We see:

conspiracy-shaped belief systems,

escalating symbolic language,

“digital soldiers” and “information warfare” framing,

legal fights doubling as media content,

monetisation through subscriptions, donations, and status,

extreme certainty paired with moral urgency,

and near-identical narratives appearing across loosely connected actors.

From this, many analysts conclude:

There must be a coordinated psychological operation.

But that conclusion skips a step.

Before asking who is running this, we should ask:

What incentives reliably produce this shape of output?

2. The basic model: attention, rent, and political payoff

We can model the incentives facing modern political and media actors with a very simple equation (The Rent Theory of Political Identity):

Where:

(A) = attention (views, followers, engagement, list size, relevance)

(m) = monetisation efficiency of attention (subscriptions, donations, ads, access, protection)

(V) = office payoff or institutional leverage (formal power, policy influence, immunity, contracts)

(p) = probability of obtaining or retaining that leverage

Two things matter immediately:

In the modern media environment, (A) is far easier to grow than (V).

You can grow (A) without ever winning office.

This creates a class of actors who rationally optimise the first term:

These are not traditional politicians.

They are retail politicians, influence entrepreneurs, movement contractors, or ideological content businesses.

They may also want office, but attention is their primary asset.

And the market tells them, very clearly, what grows attention fastest.

3. What grows attention (empirically, not morally)

Across platforms, the following features consistently outperform:

Identity affirmation (“you see what others don’t”)

Enemy-rich narratives

High emotional arousal

Certainty over nuance

Participation (decoding, sharing, “doing your own research”)

Moral urgency (“now or never”)

Conspiratorial structures are not fringe accidents.

They are efficient attention products.

That does not require:

secret funding,

foreign handlers,

or genius-level planning.

It requires feedback.

Actors who accidentally discover these features are rewarded.

Actors who don’t disappear.

This is selection pressure, not orchestration.

4. QAnon as an emergent system, not a command structure

Whatever its origins, QAnon succeeded because it combined three economically powerful features:

(1) Identity upgrade

“You are awake” is not information.

It is status.

(2) Participation loop

Ambiguity invites labour. Labour creates attachment.

The audience doesn’t just consume the narrative, they complete it.

(3) Certainty-as-reward

Belief becomes proof of belonging.

Each of these increases (A).

Together, they dramatically increase (m), because emotionally invested audiences convert.

Once these loops close, central control is no longer necessary.

The system runs itself.

5. Why coordination keeps being inferred

Here’s the cognitive trap:

When many actors optimise for the same reward function, their outputs converge.

Convergence looks like coordination.

But convergence is exactly what markets produce.

Fashion doesn’t require a secret council.

Language doesn’t require a director.

Genres don’t require a mastermind.They emerge from incentives plus imitation.

Political conspiracy narratives now behave the same way.

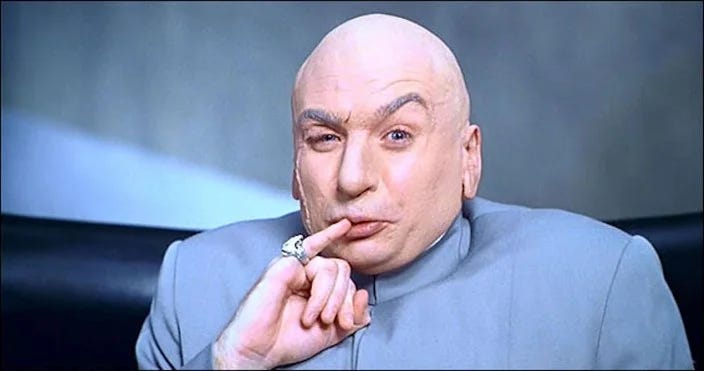

6. Exhibit A: Flynn — no psyop required to explain the behaviour

Recent analysis of Mike Flynn often frames his media output, legal activity, and rhetoric as a coordinated domestic psychological operation.

Let’s grant the facts without granting the interpretation.

Observables:

Media output using war framing and symbolic language.

Legal filings that double as culture-war messaging.

Public alignment with high-engagement narratives.

Content that resonates strongly with an existing identity audience.

None of this is in dispute.

The question is: what explains it best?

Under the rent/attention model, this behaviour is exactly what we’d predict from a high-status actor operating in a saturated attention market:

War language raises stakes → increases (A)

Symbolic ambiguity broadens coalition → increases (A)

Legal conflict generates narrative content → increases (A) and sometimes (p)

High-certainty framing increases conversion → increases (m)

You do not need:

military doctrine,

psyop expertise,

or secret coordination

to get these outputs.

You need a market that rewards them.

Calling this a “confession” or an “operation” adds drama, but it adds very little explanatory power.

7. Exhibit B: anti-Q analysis and the mirror problem

Now for the uncomfortable part.

A recent Substack investigation frames Flynn’s activity as a sophisticated psychological war, complete with decoded symbols, operational intent, and escalating threat.

Much of the description is accurate.

But the explanation mirrors the thing it critiques.

It:

escalates stakes,

interprets coherence as intent,

presents decoding as revelation,

positions the reader as “seeing the hidden layer,”

and converts urgency into subscription.

That doesn’t make it dishonest.

It makes it structurally downstream of the same incentives.

Different morals.

Same attention physics.

This is why “psyop” language spreads so easily:

it is itself a high-engagement explanatory frame.

8. Why “psyop” has become a vibes-based explanation

“Psyop” does a lot of emotional work:

It restores intentionality.

It scales the villain to match the fear.

It implies a solution (“expose the plan”).

It flatters the interpreter (“you can see it”).

But as an explanation, it is often overdetermined.

If your model requires:

decoding symbols,

inferring hidden intent,

treating ambiguity as evidence,

and escalating certainty with every artifact…

…you are no longer analysing a system.

You are participating in a genre.

My model does something more boring, and in my opinion more powerful and concerning.

9. The Russia question, settled properly

Even if Russia:

seeded early narratives,

boosted certain content,

exploited existing fractures,

that fact rapidly loses explanatory value once the system is self-sustaining.

Initial conditions do not explain equilibrium states.

After the Big Bang, gravity runs the universe, not God.

After incentive loops close, markets run the narrative, not Moscow.

Blaming foreign origin stories at this stage functions mainly as:

moral comfort,

political theatre,

and avoidance of domestic responsibility.

My model says otherwise:

This is profitable.

This is rewarded.

This is us.

10. Predictions my model makes (and passes)

A good model predicts.

This framework predicts that:

Symbolic escalation will continue without coordination.

“Psyop” language will spread to critics as well as believers.

Legal conflict will be monetised as content.

Removing individual actors won’t stop the pattern.

New movements will re-invent the same structures under new names.

All of this is already observable.

No conspiracy required.

11. Why this way is easier, and more dangerous

This approach feels easier because it removes mythology.

You don’t have to:

chase endless threads,

decode symbols,

infer intent,

or inflate villains.

You ask one question instead:

What behaviour does this reward next?

That question scales.

It generalises.

It survives actor replacement.

And it leads to a more unsettling conclusion:

This cannot be solved by exposure alone, because there is no hidden plan to expose.

12. The actual lesson

If you want to resist manipulation, don’t ask:

“What does this symbol really mean?”

“Who is behind this?”

“Is this a psyop?”

Ask:

“What does this increase (A) for?”

“How does it convert to money, status, or protection?”

“What behaviour does it select for?”

That’s not awakening.

That’s maths and economics.

Closing

If conspiracies were required to produce this world, it wouldn’t be ubiquitous.

The fact that it is everywhere is the proof that they aren’t.

The machine doesn’t need a mastermind.

It needs incentives.

And until those change, the outputs will keep looking the same, no matter who you remove from the board.

I like this. And you’re quite right, it’s reasonable to suggest that the incentives structure in the platform economy produces a certain type of discourse and, by way of it’s ‘environmental undertow’, privileges populist-style rhetoric and conspiracy theories.

Interference - which does happen, and has been empirically proven (slowly, and therefore very partially) - works best when it is opportunistic. I would cautiously suggest that state actors further east, who share a better muscle memory than those to the west, of how to operate under autocratic conditions, are better at it. They know to move slowly, and not too obviously (*cough* Musk *cough*).

They obviously see the affordances offered by the platform industry, as well as America’s (and therefore, sadly, the West’s) fetish for ‘connectivity’ and, alongside it, the assumed entitlement to exposure without consequences. Anyone with normal risk perception understands that connectivity increases exposure, and those who understand what navigation of authoritarian structures without losing one’s head or succumbing to sudden, terminal conditions entails, certainly understand it. The entire media environment presented by the platform economy puts us at risk that neither begins, nor ends, with state or non-state actors that exploit that risk (which I think is what you’re saying). Even if we addressed the particular actors causing trouble now, the incentives produced by the platform economy in its current form would invite, or even generate, new ones.

Ergo, the root problem is the incentives structure.

And the root of that, is how we arrive at the metrics that underpin monetisation. And the root of that, is how we model digital publics (whether ‘real people’ or not). And there are serviceable, if as of yet untested alternatives that are not based on identity.