When Outsiders Enter the Room

Why Attention Collapses Inside Power

There is a common assumption in politics that getting inside the room automatically generates more attention, more relevance, and more power. For decades, this assumption has mostly held. Parliament, cabinet positions, titles, these were attention multipliers.

But something interesting is happening now, and Nigel Farage offers a particularly clean case study of why that assumption is breaking down.

What we’re watching is not a personal failure or a communications blunder. It’s a structural transition, and one that punishes half-steps.

The Initial Bet: Office Equals Attention

From an outsider’s perspective, Farage’s move into Parliament looks obvious. Becoming an MP should, in theory:

Increase visibility

Legitimate grievances

Convert outsider energy into institutional leverage

And in the short term, it worked. Media attention spiked. The novelty factor kicked in. The “outsider enters the system” story writes itself.

But novelty decays fast.

What replaces it is something far less forgiving: institutional attention mechanics.

Parliament Is Not an Attention Amplifier

The House of Commons is not designed to maximise individual visibility. Quite the opposite.

It:

Rations speaking time

Enforces turn-taking

Dilutes narrative control

Contextualises every intervention

This is not a moral judgment; it’s architectural. Parliament evolved to dampen unilateral dominance, not reward it.

For actors whose power comes from attention concentration rather than coalition-building, this creates an immediate ceiling. Attention doesn’t disappear, but it becomes shared, procedural, and slow.

In other words: attention elasticity collapses.

The Pivot: Chasing Political Value Elsewhere

Once attention inside the institution plateaus, the next rational move is to increase perceived political value, electability, seriousness, plausibility.

That’s where elite recruitment comes in.

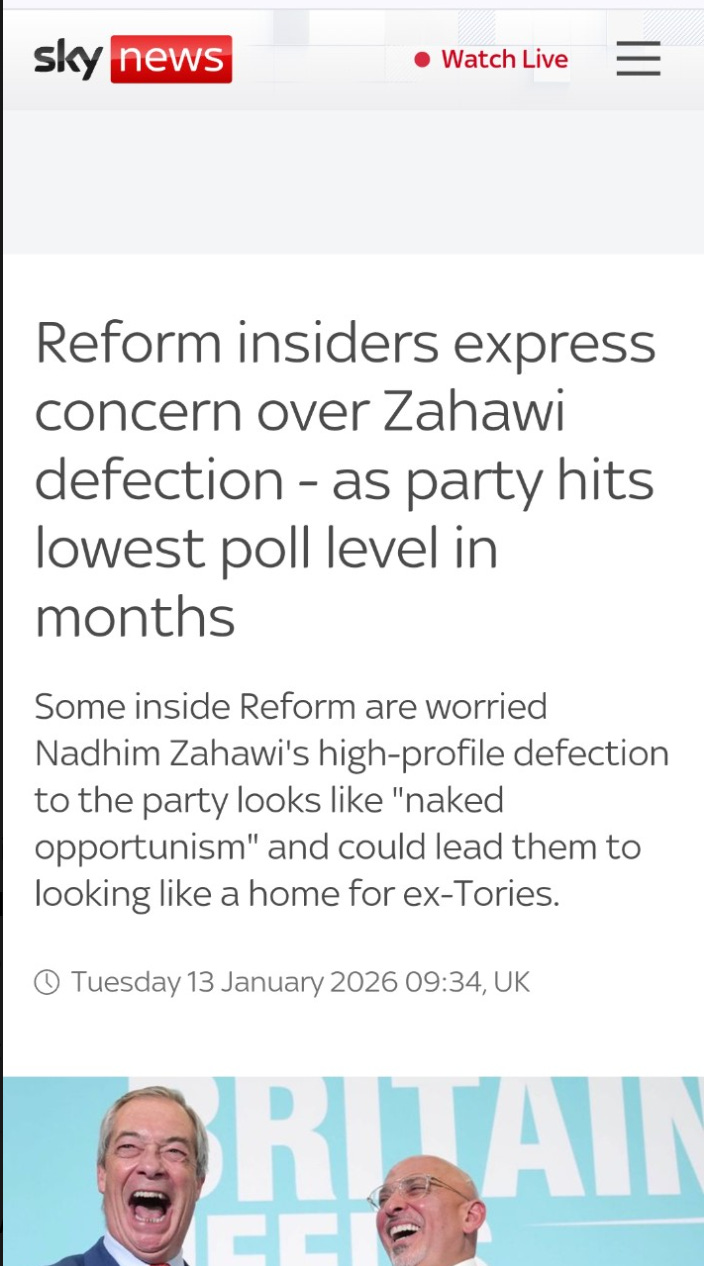

High-profile defectors. Former establishment figures. Signals of competence and readiness. The message is clear: this is no longer just a protest movement — it’s a government-in-waiting.

Again, this is not incoherent. It’s a standard strategy.

But it has an underappreciated cost.

Closed Anti-Elite Markets Don’t Survive Elite Absorption

Farage’s historical strength did not come from broad, open attention markets. It came from closed identity markets, tightly defined around opposition to elites, institutions, and insiders.

These markets have distinctive properties:

Attention is concentrated

Identity is binary (“us” vs “them”)

Leadership is focal rather than distributed

Introducing establishment figures into such a market does not simply add credibility. It dilutes attention and blurs identity boundaries.

The antagonist becomes a collaborator.

The focal point becomes crowded.

The narrative loses contrast.

What helps in open electoral markets actively weakens closed identity ones.

This is the core tension: you cannot scale political value without collapsing attention density in the markets that produced it.

Why the PMQs Stunt Matters

Seen through this lens, Farage’s recent PMQs protest isn’t erratic behaviour, it’s compensatory.

It attempts to:

Reassert personal grievance

Reclaim outsider status while remaining inside

Bypass institutional attention limits

Recentre the narrative on exclusion

But institutional settings are unforgiving. Procedural facts are easy to verify. Claims of exclusion are cheap to puncture. The result is credibility loss without meaningful attention recovery.

The system doesn’t need to suppress the stunt. It simply prices it correctly.

The Trap of Half-Transition

This is the danger zone for outsider figures:

Fully outside institutions → high attention, low formal power

Fully inside institutions → low attention, high procedural power

The worst position is in between.

Half inside, half outside means:

Institutional constraints apply

Outsider attention premiums evaporate

Credibility costs rise

Identity coherence weakens

You end up paying the costs of both worlds while capturing the benefits of neither.

This Isn’t About One Politician

The reason this matters is that the dynamic is repeatable.

Any figure who:

Builds power in closed attention markets

Enters formal institutions

Attempts to scale without abandoning identity-based rents

will face the same structural squeeze.

This is why so many “outsider” movements stall on entry to power — not because they lose beliefs, but because the attention economics change under their feet.

The Quiet Lesson

Institutions like Parliament are not obsolete. They are doing exactly what they were designed to do: resist attention monopolies.

What has changed is the environment around them.

Attention is now abundant outside institutions and scarce inside them. That inversion makes entry risky for anyone whose power depends on being singular, oppositional, and central.

Becoming an MP increases legitimacy, but it also ends the era of unbounded attention.

And once that era ends, there is no easy way back.