Protest Songs 7 - A love letter to Britain: Brilliant Songs, Broken Systems

Lying flat, British style, and why our Post Office is a disgrace but our music is astonishing

Britain has a peculiar talent.

We produce some of the most emotionally precise, globally influential music of the modern age and we do it while systematically refusing to confront institutional failure, technological change, and our own complicity in letting things quietly rot.

This is not a paradox to be resolved.

It is the defining contradiction of British culture.

We sing clearly about what hurts.

We complain endlessly about what’s broken.

And then we politely stop short of reckoning.

British creativity thrives despite this habit — not because of it.

This is a love letter to British music.

It is also a baffled, affectionate attempt to describe why a country capable of such honesty in art remains so evasive everywhere else.

Lying Flat, British Style

In China, “lying flat” is a refusal to perform the system’s expectations.

No slogans. No marches. Just opting out.

Britain has been doing its own version for decades.

Not dramatically.

Not confrontationally.

But quietly, sideways, and with humour.

It looks like:

standing in the kitchen at parties

choosing irony over outrage

opting out without leaving

endurance without belief

humour as camouflage

Not rebellion just non-participation.

“I’m here,” it says,

“but I’m not playing along.”

This is the emotional operating system behind an enormous amount of British art.

It keeps people sane.

It does not fix institutions.

And in that tension, is where British music lives.

Ghost Town — The Specials (1981)

Collective collapse, seen clearly and ignored anyway

If there is one song that captures Britain’s relationship with institutional failure, it is Ghost Town.

This is not metaphor.

It is reportage.

Closed shops.

Youth unemployment.

Aggressive policing.

Communities hollowed out and blamed for their own disappearance.

“This town is coming like a ghost town.”

Not might.

Not could.

Is.

The Specials did not romanticise decline.

They named cause and effect.

Britain heard it.

Britain danced to it.

Britain agreed it was very true.

And then Britain largely chose not to act.

This is the pattern.

A New England — Billy Bragg (1983)

Endurance without illusion

Billy Bragg understands British limits.

He doesn’t pretend people are about to rise up.

He sings from bedsits, train platforms, rented rooms — the geography of staying put.

“I don’t want to change the world

I’m not looking for a New England.”

This is not resignation.

It is honesty.

Bragg documents the emotional cost of living in a country that quietly narrows your horizons while insisting you’re lucky to have them.

A protest song for people who know exactly what’s wrong

and also know they still have to get up for work tomorrow.

Working Class Hero — John Lennon (1970)

Naming the machine

Lennon’s achievement here is clarity.

Working Class Hero is an anatomy lesson in how Britain manufactures obedience, aspiration, and shame: humiliation as education, conformity as virtue.

“A working class hero is something to be.”

Not encouragement.

A warning.

Britain loves the song.

Quotes the lyric.

Rarely applies the lesson.

Once again, art does the work institutions avoid.

Drop the Pilot — Joan Armatrading (1983)

Refusal as survival

Armatrading arrived from the Caribbean into Birmingham: rain, industry, racism, restraint.

Her protest was quiet but radical:

I will not make myself smaller to make you comfortable.

Drop the Pilot is autonomy in a culture that constantly pressures people, especially women, especially Black women, to manage other people’s expectations.

No complaint.

No apology.

Just selfhood.

That, in Britain, is subversive.

I Don’t Like Mondays — Boomtown Rats (1979)

Collapse without spectacle

Bob Geldof took an American tragedy and stripped away the spectacle.

What remains is numbness.

Shaped by grey Dublin and grey Britain, he understood that the danger isn’t chaos: it’s monotony, repression, and systems that don’t notice when people break.

“Tell me why I don’t like Mondays.”

Not a question.

A symptom.

Common People — Pulp (1995)

The lie at the heart of British nostalgia

If Ghost Town names collapse, Common People punctures something more intimate:

Britain’s habit of romanticising hardship while refusing its consequences.

This is poverty as aesthetic.

Struggle as cosplay.

Jarvis Cocker doesn’t lecture.

He waits.

And lets the fantasy collapse.

Because Britain is very good at talking about class

and very bad at confronting how class actually works.

We love grit.

We love authenticity.

We struggle with accountability.

Common People says the quiet part out loud and still hurts because the behaviour never stopped.

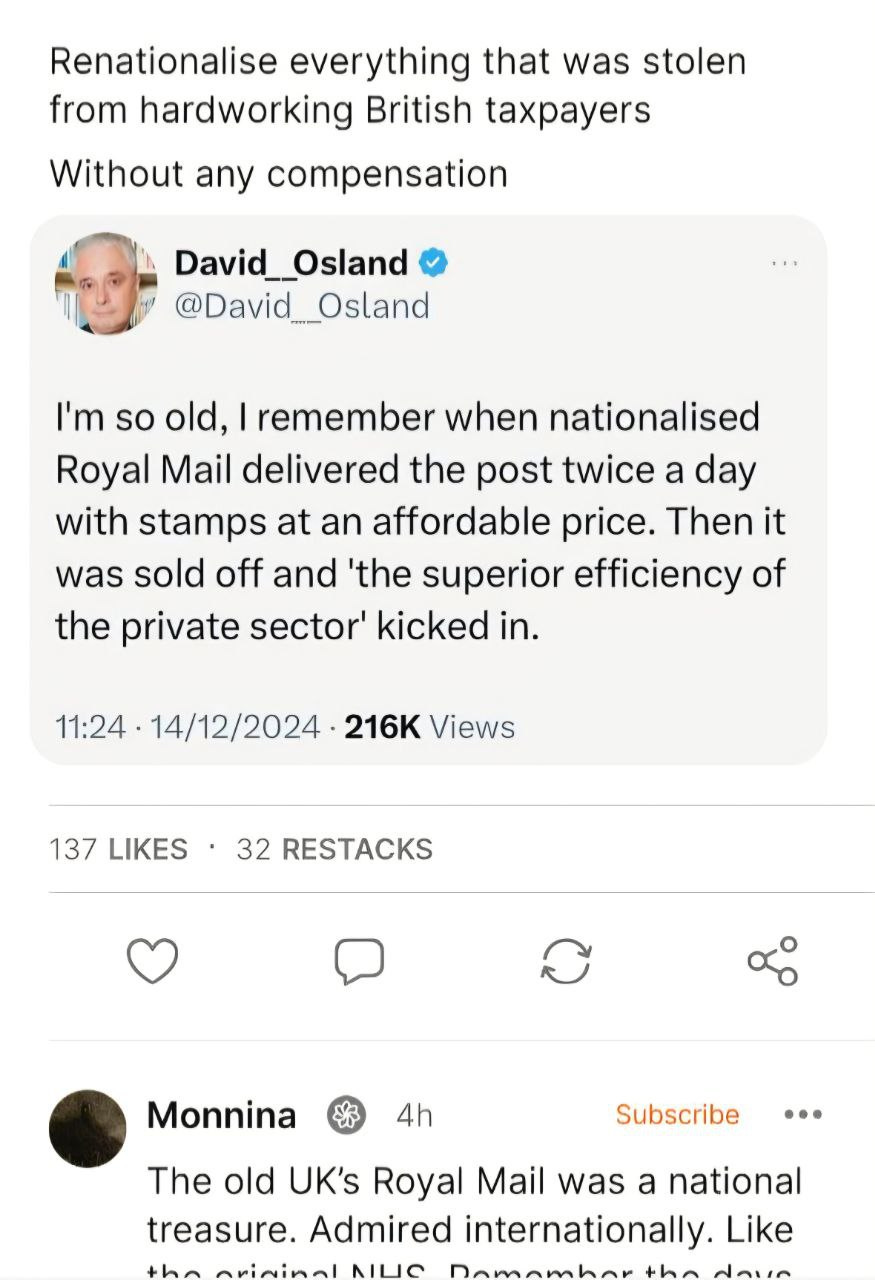

The Post Office Problem

When nostalgia replaces reckoning

This is where the music and the country finally part ways.

Ask British people about the Post Office (or Royal Mail) and the response is almost always the same:

nostalgia

sadness

affection

a vague sense of loss

“It used to be brilliant.”

“It held communities together.”

“It’s such a shame what’s happened.”

All of this sounds humane.

None of it is honest enough.

Because what is being remembered fondly is not an institution — it is a feeling.

And that feeling has been used, repeatedly, to avoid moral reckoning.

For decades, the Post Office:

destroyed lives

criminalised its own workers and drove them to suicide

denied reality in the face of overwhelming evidence

weaponised bureaucracy

hid behind reputation, tradition, and public affection

And when the truth finally emerged, the dominant national response was not fury.

It was melancholy.

“Isn’t it awful what’s happened to it.”

Not: Who allowed this?

Not: Why did this go on for so long?

Not: What does this say about how we treat institutions we feel fond of?

Just… sadness.

This is moral laundering.

It turns structural violence into wistfulness.

It allows people to feel compassionate without feeling responsible.

It lets institutions fail catastrophically while remaining emotionally protected.

And this, crucially, is exactly what British music refuses to do.

Why the songs won’t let us off the hook

Ghost Town doesn’t sigh sadly about boarded-up shops.

It names collapse.

Common People doesn’t admire hardship.

It exposes moral tourism.

Working Class Hero doesn’t romanticise class.

It maps the machinery.

British music does not confuse affection with absolution.

It understands something the culture struggles with:

You can love something and still hold it accountable.

The Post Office shows what happens when we don’t.

From institutional failure to the kitchen

And here is where the connection to lying flat becomes unavoidable.

When people realise that institutions:

won’t listen

won’t change

won’t admit fault

and will be protected by nostalgia

they don’t revolt.

They withdraw.

They lower expectations.

They stop demanding.

They protect themselves.

They complain, and then they adapt.

They end up in the kitchen at parties.

The same instinct that shrugs “it’s such a shame what’s happened”

is the instinct that says:

I’m not going to burn myself out trying to fix this.

I’ll survive instead.

That instinct keeps people sane.

It does not fix systems.

And that is the tension at the heart of this entire article.

You’ll Always Find Me in the Kitchen at Parties — Jona Lewie (1980)

Lying flat, British style — with a mug of tea

If China has “lying flat,” Britain has been practising its own version for decades.

It just never gave it a name.

Jona Lewie did.

You’ll Always Find Me in the Kitchen at Parties is not a protest song in the traditional sense. There is no demand, no slogan, no villain, no hope of reform. It doesn’t rage against the system or even name it.

It simply opts out.

The narrator is present but disengaged.

Sociable but not participating.

Watching rather than performing.

Choosing the kettle over the dancefloor.

“You’ll always find me in the kitchen at parties.”

This is not shyness.

It’s not awkwardness.

It’s withdrawal as self-preservation.

A refusal to play the social game without making a scene about it.

This is British “lying flat” in its most distilled form:

I am here, but I am not performing for you.

Why this hits so hard in Britain

In a culture that distrusts grand gestures and finds open refusal embarrassing, the most viable form of resistance is sideways.

You don’t storm out.

You don’t shout.

You don’t demand.

You drift.

You make tea.

You stand by the fridge.

You listen.

You observe.

You keep your dignity intact by lowering your level of engagement.

Lewie isn’t mocking parties.

He’s documenting a coping strategy.

One that millions of British people instantly recognise without needing it explained.

This is not rebellion: it is survival

That’s the crucial distinction.

British “lying flat” does not seek to change the system.

It seeks to outlast it.

It protects the individual.

It does nothing to fix institutions.

And this is where the song connects directly to everything else in this essay.

The same instinct that puts someone in the kitchen at a party is the instinct that:

complains nostalgically instead of confronting

withdraws emotionally instead of demanding accountability

survives institutional failure by shrinking expectations

accepts broken systems as weather

The kettle goes on.

The music plays.

Life continues.

This is how Britain copes.

It is gentle.

It is funny.

It is humane.

Why this song deserves it’s place alongside John Lennon, Ghost Town and Common People

Ghost Town names collapse.

Common People punctures moral tourism.

Working Class Hero names the machinery.

Kitchen at Parties explains what happens after.

After the insight.

After the disappointment.

After the realisation that nothing is going to change quickly.

You don’t riot.

You don’t leave.

You put the kettle on.

You choose non-participation over confrontation.

You lie flat, British style.

Why this makes the music even more important

Because when people withdraw quietly, the only place truth can still surface is art.

Music becomes the space where feelings are allowed to exist openly, even when life requires understatement.

That’s why Britain keeps producing songs that are devastatingly accurate about emotional reality while remaining evasive about institutional responsibility.

The people step back.

The songs step forward.

And somewhere, at the edge of the room, next to the mugs and the biscuits, someone is nodding along, thinking:

Yes.

This is exactly it.

That is not apathy.

That is endurance.

And it may be the most British form of protest we have ever invented.

The Inanity of Daily Life as Cultural Engine

And the Americans Britain quietly set free

Look again at the artists shaped by this island’s drizzle, restraint, and emotional repression.

British-born revolutionaries

The Beatles

David Bowie

Elton John (Reg Dwight: Watford’s greatest cosmic accident)

Joy Division / New Order

Depeche Mode

Erasure

Black Sabbath

The Smiths

Queen

Billy Bragg

Joan Armatrading

John Lennon

These are not products of confidence.

They are products of pressure.

But here’s the deeper truth:

Britain also shapes the people who weren’t born here.

It gives outsiders, Americans especially, something their homeland often cannot:

permission to be strange

permission to experiment

permission to fail

It gives them British emotional weather.

Jimi Hendrix — became Jimi Hendrix in London

Hendrix did not become himself in America.

He became himself here.

Britain: grimy, grey, hungry, looked at him and said:

Yes.

Do that.

Be louder.

America only realised what it had after Britain reflected it back, amplified.

Sparks — perfected by UK eccentricity

Too strange for America.

Perfect for Britain.

Ron and Russell Mael weren’t parodying British music, they were completing it.

The UK rewards strangeness in art while repressing it in daily life.

A contradiction that turns out to be enormously productive.

Other Americans shaped by British oddness

Tina Turner rebuilt her career here

Nina Simone found refuge and dignity

The Ramones were crowned here first

Bob Dylan absorbed British melancholy

Paul Simon recalibrated in early-60s London

America produces the raw brilliance.

Britain weirds it into something new.

Mr Brightside — The Killers (2003)

American anxiety rewritten as British ritual

There is no reason this should be a British anthem.

And yet.

Britain heard panic, repression, internal monologue, and sang it communally, at weddings.

Not performance.

Confession.

Glastonbury citizenship granted.

Take Your Mama — Scissor Sisters (2004)

Joy as refusal

Camp, sincere, joyful; everything Britain pretends to distrust.

And yet embraced.

Because beneath the glitter was something deeply British:

awkward family reconciliation, humour as survival, joy without apology.

Outsiders adopted.

Permanent residents.

Olivia Rodrigo: Union Jack hotpants, jacket potatoes, and being adopted by drizzle

Every few years an American superstar wanders into Britain, expecting… I don’t know, castles and cool accents, and maybe a polite cup of tea.

And instead they get Glastonbury, a field of mud and feelings, and a nation that processes emotion primarily by singing in unison while pretending it’s a laugh.

Olivia Rodrigo fits this tradition perfectly.

She headlined Glastonbury, turned up in Union Jack hotpants, and in doing so performed the most American act imaginable: wearing British symbolism with total sincerity, as if it’s normal, as if the Union Flag isn’t something half the country is faintly embarrassed by and the other half owns in bulk.

Britain loves this. Not because it’s patriotic, Britain isn’t really patriotic in a clean way, but because it’s earnest. And earnestness, when it comes from an outsider, is often easier for us to tolerate than when it comes from ourselves.

Then came the detail that completes the portrait: the boyfriend lunch story.

Olivia, incredibly rich, generously offering to buy lunch, the sort of casual LA magnanimity that assumes lunch involves choice, abundance, and a non-tragic amount of seasoning, and her British boyfriend opting for something so profoundly, aggressively domestic it feels like a ration book with a Spotify account:

jacket potato and beans.

Not “a sandwich.”

Not “some sushi.”

Not “a salad.”

Not “a little place I know.”

A hot potato.

With beans.

This is the culinary equivalent of British “lying flat”: comfort over performance, familiarity over aspiration, dignity maintained through deliberately low expectations. It’s not austerity exactly, it’s something older and stranger: a kind of emotional thrift.

And it explains why Britain “gets” Olivia Rodrigo.

Because her songs are already full of the British emotional register: heartbreak, embarrassment, melodrama, self-awareness, the internal monologue that spirals while the face stays composed. She writes like someone who understands that the real catastrophe isn’t what happened, it’s how long you will replay it in your head afterwards.

So Britain adopts her.

Not because she’s trying to be British.

But because she’s accidentally arrived fluent in the emotional weather (pun intended), and the boyfriend’s beans-on-spud moment proves she’s now living inside it.

That’s the UK deal with outsiders: we don’t change you by force. We just let you date someone who orders jacket potato and beans like it’s a normal choice, and suddenly you understand the whole country.

Why this chaos is a love letter to Britain and its music

Because none of this comes from hatred.

Britain saved families like mine. Quietly. Bureaucratically. Without theatre. It made space where history had offered none: shelter, then belonging, then voice.

And it gave us the music, the place where honesty survived when public language failed.

British creativity is not a substitute for accountability. It is a warning system that keeps going off. The songs are the smoke alarm, the pressure valve, the civic conscience we outsource because directly naming things is considered “making a fuss”.

The tragedy is not that Britain complains.

It’s that Britain mistakes complaint for reckoning.

We are world-class at saying “isn’t it a shame” and then carrying on exactly as before. We treat institutional failure like weather: regrettable, familiar, not quite anyone’s job to fix. The Post Office proves what happens when nostalgia protects a system from moral scrutiny. The music proves we understand perfectly well what’s happening, we just struggle to bring that honesty into daylight.

And yet, the songs keep coming.

That’s the miracle. That’s the inheritance. That’s the point.

Lennon didn’t just diagnose the machine. He also modelled the national response: tea, bed, and refusal to perform.

So the most radical act is still this:

to lie flat, British style —

to refuse performance,

to feel clearly,

and to sing the truth out loud

while standing quietly by the kettle.

And yes: my biggest worry is that if British people ever stop complaining, the music will become crap.

Lying flat now I have a term for it. Finally!!! I’m not finished reading lol 😝

Moral laundering. Good one!