I burnt down your house so we can live together

Russia as the crazy girlfriend meme

1. Imperial Russia: The ‘Little Russians’ Myth

In the 18th–19th centuries, the Russian Empire classified Ukrainians not as a distinct nation but as “Little Russians” (Malorossy), a branch of the Russian people.

The “brotherhood” framing was used to deny political independence — brothers live under one roof, after all.

Ukrainian language, literature, and cultural expression were systematically suppressed (e.g., the 1876 Ems Ukaz banning publications in Ukrainian) under the pretext of preserving “unity” in the “Russian family.”

Key idea: The “brotherhood” myth was always asymmetric, one brother was the “elder” (Russia), the other the “younger” (Ukraine) who must obey.

2. Soviet Era: The Propaganda of Socialist Brotherhood

After Ukraine was forcibly incorporated into the USSR, propaganda heavily pushed the term “brotherly peoples” (дружба народов — “friendship of the peoples”).

It served to gloss over the fact that Soviet control was maintained by force — mass arrests, famine (Holodomor), and suppression of dissent.

State media presented Moscow as the benevolent big brother, guiding Ukraine along the “correct” socialist path.

Criticism of this narrative was criminalized as “bourgeois nationalism.”

Parallel to today: Anyone rejecting the “brotherhood” framing could be smeared as anti-Russian or anti-peace, exactly the dynamic this tweet plays into.

3. Post-Soviet Period: ‘We’re Family’ as a Soft Power Tool

After the USSR collapsed, Kremlin-aligned politicians continued to invoke the “brotherly nations” idea to resist Ukraine’s Western integration.

Putin revived it explicitly in the early 2000s, portraying Ukraine’s orientation toward NATO and the EU as a betrayal of familial bonds.

The phrase peaked in propaganda during 2014’s Crimea annexation. Putin said Russians and Ukrainians are “one people,” implying separation is artificial and reunification is natural.

Translation: “Brotherhood” is code for “you don’t really have sovereignty.”

4. 2022 Full-Scale Invasion: The Weaponized Family Drama

On the eve of the invasion, Putin delivered a speech again framing Russia and Ukraine as “one people,” blaming the West for “turning brothers against each other.”

Russian state TV pushes this constantly, portraying Ukraine’s resistance as a tragic misunderstanding, not a legitimate defense against invasion.

This lets propagandists depict Russian military aggression as a “family dispute” that outsiders should not interfere in.

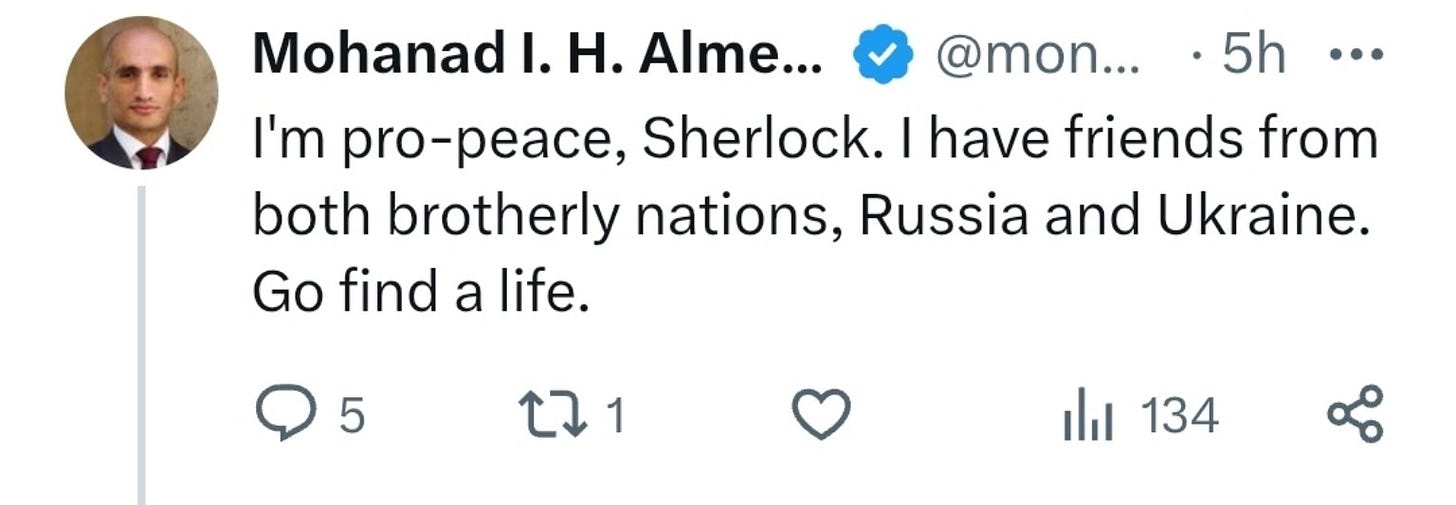

The rest of this substack is dedicated to this Lawyer from UAE he owns Polaris.ae

5. The Setup: “I’m pro-peace” as a shield

The “I’m pro-peace” opener is a rhetorical trick. It attempts to inoculate the speaker from criticism by presenting themselves as morally superior, someone who just wants peace, while dodging the moral responsibility to name the aggressor. In propaganda analysis, this is called moral deflection.

In reality, “pro-peace” in this context is used to mask an alignment with a status quo where the aggressor (Russia) keeps its gains. It’s the same move used during the Cold War by Soviet-aligned “peace” groups who opposed NATO deployment but never criticized Soviet invasions.

6. “Both brotherly nations”, a Kremlin-coded phrase

As we have seen Moscow has used “brotherly peoples” rhetoric since Tsarist times to frame Ukrainian resistance as “betrayal” and to delegitimise Ukrainian nationhood. In 2014, Putin invoked this exact language to justify the annexation of Crimea.

7. False equivalence as moral sabotage

By lumping both Russia and Ukraine together as equally “brotherly,” the statement obscures the fact that one side is the invader and the other the victim. This is classic false balance, placing both on the same moral plane when one is committing mass atrocities and the other is defending its existence.

It’s equivalent to saying “I have friends on both sides” during an armed robbery while ignoring who’s holding the gun.

8. Gaslighting through the friendship claim

The “I have friends from both” line is emotional gaslighting. It reframes criticism of enabling narratives as a personal attack (“you’re saying I can’t care about my friends”), when in reality the issue is the rhetoric that justifies aggression.

It’s designed to make critics seem unreasonable or hateful, as though they’re against friendship or empathy itself, rather than against the manipulation of language to support war propaganda.

9. The hostile closer: “Go find a life”

Ending with “Go find a life” shifts from faux-moral superiority to open hostility, another tell-tale sign of bad-faith engagement. It reveals that the “pro-peace” posture was never genuine; it was a performance designed to shut down criticism while smuggling in Kremlin talking points.

Why it’s a disgusting lie

It misrepresents the reality: Ukraine is not engaged in a symmetrical conflict with Russia; it is defending itself from a full-scale invasion.

It launders Kremlin narratives into Western discourse under the cover of neutrality.

It gaslights critics by reframing opposition to propaganda as opposition to friendship or peace.

It normalizes occupation by pretending the aggressor and victim share equal blame and should simply “make peace”, on the aggressor’s terms.